“That Blessed Pocahontas”

“In the utmost of many extremities, that blessed Pocahontas, the great Kings daughter of Virginia, oft saved my life.” (A True Relation of Virginia, p. 40)

“… a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was two great stones were brought before Powhatan. Then as many as could laid hands on him [Smith], dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head; and being ready with their clubs to beat out his brains, Pocahontas, the king’s dearest daughter, when no entreaty could prevail, got his head in her arms and laid her own upon his to save him from death; whereat the emperor was contented he should live …” (The Generall Historie, p.49)

Ever since historian Henry Adams over a hundred and fifty years ago decided to take potshots at Smith’s veracity and character, others have routinely stepped up, piled on, felt free. Within a generation along came Alexander Brown. Brown was like a Gabriel Archer redivivus. His whole purpose as a Jamestown historian, he tells us, was to rescue the true record from Smith’s lies, distortions, fabrications, slanders. Brown offered various “proofs” beginning with the Pocahontas rescue.

Even Smith supporters have come to feel they must apologize for the story that appeared in full in 1624 as a case of misinterpreted ceremonial symbolism, at best. A common opinion puts it that his life was not being saved, he was being “initiated” into Powhatan’s tribe, to be given his daughter as a wife and a town to be chief of at Capahosic. Besides, didn’t some Spaniard in Florida have the same experience?

Popular historian Bernard DeVoto, on page 25 of his bestselling The Course of Empire (1952), writes, “Juan Ortiz … sent on a ship by the widow of Narváez to search for traces of the lost company, had survived in Florida [11 years, 1528–1539]. Coastal Indians … enticed him and several others ashore. They killed the others but spared him.” He adds in a parenthesis, “The story is so like that of John Smith’s deliverance by Pocahontas that it may be the original.” Ortiz comes to us from an account of the De Soto expedition written by “a gentleman of Elvas.” The English version appeared in Purchas in 1609, so DeVoto wants to suggest that Smith read it there and appropriated it for use in his General History a decade and a half later. The chief’s daughter begs her father to spare Ortiz from being roasted alive.

The best defense of Smith is in Leo Lemay’s 1992 book devoted to the subject, Did Pocahontas Save Captain John Smith?, since it seems by now to have required a book. In a leisurely set of rebuttals, Lemay points out that none of the Indians living in London when General History appeared raised any eyebrows. Undoubtedly some of them witnessed the event at Werowocomoco or knew of those who had. (Tomocomo, where were you?) It is a clue missed by every other historian. But Lemay scores so many other points he demonstrates that denying the story creates more difficulties for the historian than accepting it.

For that matter, if the Ortiz story is true, why shouldn’t it make Smith’s story all the more believable as “typical treatment by Indians from Virginia to Florida.” But Ortiz notwithstanding, there’s little reason to doubt Smith anyway.

The immediate aftermath of the rescue saw Pocahontas on the scene at the fort for the first time and eager for the role of protectress. She begins sending ample and much-needed supplies of food to Jamestown and befriends the English at every turn thereafter. We also find her interceding for Paspahegh captives held at Jamestown for theft. Smith grumbles but grants their release. What but reciprocity?

Another time she risked her life to save him and his party by warning them of an ambush at Werowocomoco. Smith tells us she risked hiding Richard Wyffin to prevent his capture and reportedly saved the life of Henry Spelman, a prisoner of the Patawomecks, while she and he were living among them. A pattern emerges in this young lady of intercession and peacemaking.

Smith, as many observe, gave details of the rescue story rather late after omitting to do so in earlier accounts of his month-long capture. In 1608 his True Relation was a straight and plain account. In 1624, wasn’t it time to spruce it up into an adventure tale? Perhaps, but a gag rule might also explain the change from guarded tone to frank and full details. Hair-raising stories of native savagery were in the early days of the settlement regularly censored and discouraged by the London Company in reports from Virginia.

It was a good idea for him to tone it down for another reason. He tells us many suspected him of angling to be a favorite, even the husband, of Powhatan’s little princess, an act of dangerous presumption by the son of a yeoman and downright usurpation by a fellow colonist. By 1624, Pocahontas had been dead seven years.

Young Pocahontas sharing food with the Jamestown settlers as depicted by sculptor Adolf Sehring, on display in Gloucester, Virginia.

(Photo: Connie Lapallo)

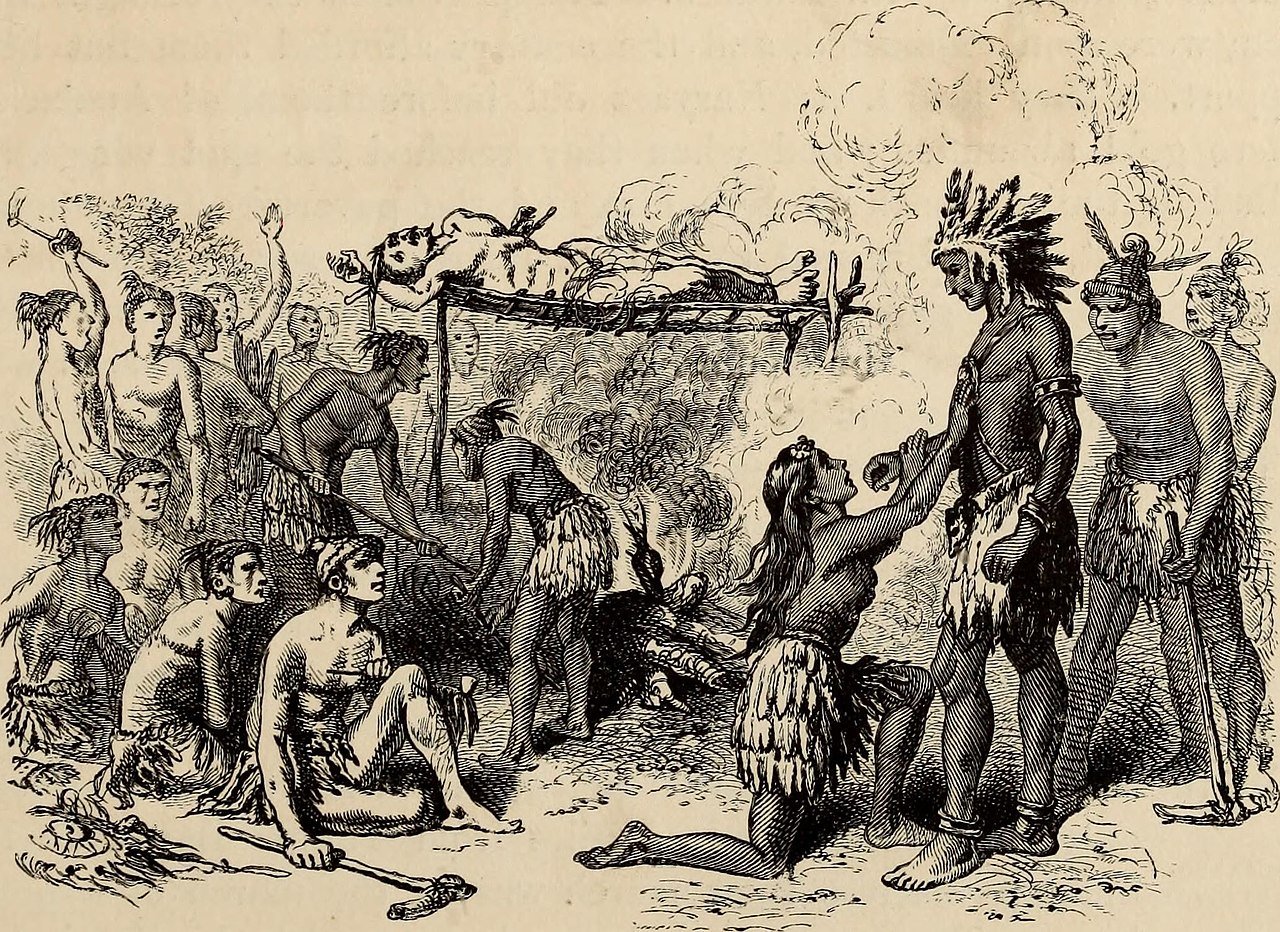

An artist’s depiction of Pocahontas saving Capt. John Smith.

Uzita chief’s daughter helping Juan Ortiz to escape. The similarities between this earlier story and Pocahontas saving Smith are obvious.